This is the final part of a four-part series addressing the question, “Is the idea of hell – an eternity of suffering apart from God – compatible with the idea of an all-good and loving God?” Up to this point, we’ve seen how (1) we humans have a craving for the good, and that this craving is literally insatiable with earthly realities; (2) that this insatiability is either a curse, or a sign that our hearts are made for something infinitely greater than earthly realities; and (3) that there are many good reasons to believe that God is the infinite good who alone can satisfy our hearts. No we’re left with the final question: what does this mean for the possibility of hell?

IV. The “Limits” of God’s Power

So that’s the case for Heaven: that God can fill the longings of the human heart. But it’s also the case for hell: God alone can fill the longings of the human heart.

God is all-good and omnipotent, which means that He wants to, and can, satisfy the longings in the hearts that He created. But why doesn’t God create a world in which we’re happy with something othan Him? His might doesn’t include the ability to do the logically impossible. C.S. Lewis explains it this way:

His Omnipotence means power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to Him, but not nonsense. This is no limit to His power. If you choose to say “God can give a creature free-will and at the same time withhold free-will from it,” you have not succeeded in saying anything about God: meaningless combinations of words do not suddenly acquire meaning simply because we prefix to them the two other words “God can”. It remains true that all things are possible with God: the intrinsic impossibilities are not things but nonentities. It is no more possible for God than for the weakest of His creatures to carry out both of two mutually exclusive alternatives; not because His power meets an obstacle, but because nonsense remains nonsense even when we talk it about God.

In other words, God can’t make a square circle, because that’s a meaningless sentence to anyone who understands their meaning. Aquinas goes a bit further, saying:

Now nothing is opposed to the idea of being except non-being. Therefore, that which implies being and non-being at the same time is repugnant to the idea of an absolutely possible thing, within the scope of the divine omnipotence. For such cannot come under the divine omnipotence, not because of any defect in the power of God, but because it has not the nature of a feasible or possible thing. Therefore, everything that does not imply a contradiction in terms, is numbered amongst those possible things, in respect of which God is called omnipotent: whereas whatever implies contradiction does not come within the scope of divine omnipotence, because it cannot have the aspect of possibility.

Why bring any of this up? Because if we’ve established that God is infinite Good, then it should be clear why the question “why doesn’t God create another infinite good” is illogical. You can’t have two contrary infinites. Heaven is a participation in the infinite goodness of God, but this would be asking for an infinite goodness apart from the infinite goodness of God.

Even created goodness is ultimately from God. Trying to have good, even a little of it, without God, is like deciding that you don’t need the sun because you have a space heater in your room. Eventually, you’re going to realize that the space heater is powerless without the sun. And so just as a solar system without the sun would quickly turn cold, so too would a life without God and the good things He creates and sustains.

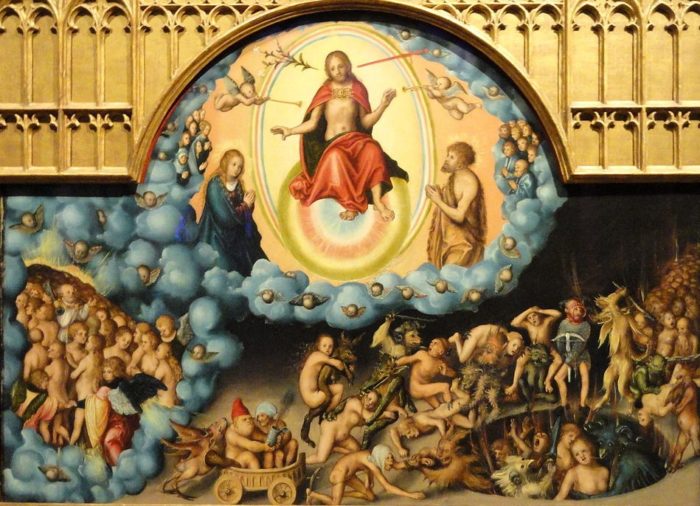

When we talk about hell, we’re talking about the ability for human beings to decisively reject God, or to choose something other than God over Him. In other words, to choose some apparent or lower good over the perfect Good, and to do so in a permanent way. As Christians, we pray that this doesn’t happen. We pray that God will do everything in His power to turn the hearts of people towards Himself, so that no one will make such a terrifying choice. But assuming that it does happen – that a person does freely and permanently reject Him – the question of hell is really this: what would it be like for us, as human creatures, to spend all eternity apart from the only satisfaction for our hearts? The answer would seem to be something very much like Erysichthon or the hungry ghosts.

So it’s not the case that the existence of hell is incompatible with a God who is perfectly good. On the contrary, the infinitude of God’s goodness is part of why we believe in hell. Pope Francis talks about how “Our infinite sadness can only be cured by an infinite love.” But this means that if we freely reject God’s infinite love, we’re left only with our own infinite sadness. More positively, this message means that we’re not damned to be hungry ghosts. A greater love than we’ve known, a love singularly capable of saving and satisfying us, is freely offered in Jesus Christ.

P.S. If you’re interested in hearing more on this theme, I spoke with my co-host Chloe Langr about it in the latest episode of The Catholic Podcast.

I have a concern regarding the statement “We pray that God will do everything in His power to turn the hearts of people towards Himself.”

If we are Thomistic or Augustinian, it is simply true that God does not do everything in his power to turn the hearts of people towards himself. In fact, there is good reason to think the majority of human beings end up in hell. That means, in most cases God does not do what it takes to save these individuals. Now you could simply dismiss this theology. But there are powerful arguments for thinking along these lines. So I am not sure how to address the fact that within Catholicism there are important traditions that make a theodicy for hell extremely difficult.

Second, even if we are not Thomistic or Augustinian, is it true that God does everything in his power to save us from hell? Maybe. But this seems like a hard pill to swallow given the evidence. It seems like an omnipotent God could do a lot more to bring people to heaven. What do you think ?

I guess your statements must also apply to the angels and demons. And, the question might be asked, did God do everything He could to keep the demons from falling away?

Being that God is all Good, who can doubt that He did? We just don’t have the wisdom to comprehend such mysteries, and I doubt that common philosophy will help in this. The words and holy examples of Christ are probably better for teaching on such subjects.

By the way, that ‘angels rejoice over one repentant sinner’ says a lot about the gift of ‘free will’ that God’s creatures have been given.

Free will is truly God’s cutting edge technology. For the great good of created free to exist necessitates realistic options from which to choose. God just can’t overwhelm other created goods including the self as alternatives. We all get everything we need and much more to draw us to God as our choice, but there are always going to be those who chose otherwise. They give glory to God in testifying to the reality of created free will as well as God’s justice and mercy.

Free will is a little bit of an “escape hatch,” which DOES answer the question, but the actual objection.

Without getting into how God could be completely sovereign (He controls all externals and even internal, psychological processes in our minds) but yet men have free will, I prefer to ask a better question.

Why even let some people, who are damned, to be born? THe principle of not violating free will, as a metaphysical impossibility, does not address that it is clearly in God’s power to snuff out the wicked and demons before they ever chose their wickedness. This is patently obvious. Its is better for many (perhaps even *most*) that they never be born, period (Matt 26:24). So…why let them be born? Why create Satan, knowing he would fall?

Free will cannot answer such an objection. Luckily, Saint Augustine already anticipated it: “God deemed it better to make good out of evil than not to permit evil to exist.”

And, if the temporary or finite existence of evil (or a “privation of good” as evil has no substance) is better than it not existing at all, then we should praise God for it. I think this is what Rom 9:22-23 is getting at.

God bless,

Craig

An element of your third paragraph reminds me of the wheat and tares. Abbot Vonier, in his booklet, “The Life of the World to Come” also struck a few chords in this context (I’m reading it today.) One example: Two men intensely dislike, and actually hate each other. What will their relationship be in heaven? DUH! They won’t be there. The fact that we are confronted with insufferable people in our lives provides the opportunity to learn to love as God does, He who came to save us while we sinned. Vonier talks of this as a ‘burnishment’, something akin to Paul’s Romans 5:4. One man may be damned (as foreseen and allowed, thereby predestined to hell) but God allows his existence for the sake of a better man on his way to salvation. Weird but logical, I think. What say you?

I agree. Being that none of us can be all-good (that would be God alone), goodness exists in degrees. And for there to be degrees, there needs to be negations of a sort.

Also, to speak less mechanically, I would say that degrees help us appreciate everything more. Summer makes me appreciate winter and vice versa. I see the beauty in both. So, if forgiveness is a good, would a good be lacking without there being anyone to forgive? If privation is a negative, then without privation how can there be appreciation?

You go crazy thinking about it.

Crazy is okay if it spirals up to Him.

God bless.

Maybe it will be less crazy after 25 billion years in Heaven? 🙂

I described free will as cutting edge technology precisely because of the paradox of God’s sovereignty. I think paradox, because my own sense of self is as one free to chose. Unlike God’s, human free will exists within a limited framework/environment. I assume this also applies to angelic free will. In our case, it includes limited knowledge, a limited set of choices and internal/external influences/pressures including powerful passions, compulsions and habits/addictions, many of which we ourselves cultivate one way or the other. This makes free choice other than God possible. Perhaps “divination” of those in heaven, is actually God’s opening of the saints framework to enjoy His unlimited existence.

With regard to the damned, when I was in 8th grade confirmation class, I asked the question of why God in His Mercy just doesn’t create those He knows will damn themselves. (This is the same kind of thinking that promotes abortion and euthanasia). I didn’t get a satisfying answer then. I later asked a Jesuit religion teacher in high school and he responded with another question, “Do people go to Hell because God knows it, or does God know it because they chose to go there?” It seems to me that those who chose Hell embrace a monstrous self satisfaction (pride) that trumps their misery. We’re made for divination and damnation is what existence becomes for those who refuse it. Such a burned out existence is still existence, which is God’s essence and therefore good (better than non-existence). Even the damned acknowledge God’s Power, but refuse to acknowlege His Mercy. Also, it would be contradictory to claim free will choices that include damnation, without actually allowing real examples of damned souls.

Yesterday I was listening to the discussions with Patrick Madrid on Relevant Radio regarding suicides and damnation. When considering the mitigating factors, it seems to me that there is a significant distinction between a motivation of despair taking the form of (eternal) self punishment as would appear to be the case of Judas, and one of immediate relief of one’s pain and suffering. In the later case, how many people are actually rejecting God’s love and mercy, rather trusting that their burden will be lifted? I’m not proposing this to minimize the seriousness of suicide, rather as cause for hope and prayer for those souls. The risk of ultimate despair cannot be minimized and engaging the pain and suffering with God’s grace is certainly the heroic and meritorious choice and opportunity.

God respects our free will and within that freedom extends to everyone sufficient grace to be saved. God may in reality grant more saving grace to someone who ultimately rejects the grace than to one saved. To be saved we must freely correspond to God’s saving grace.

God the Son, Jesus Christ, suffered excruciating agonies and humiliation when He died on a cross like a common criminal. His life set an example of self-sacrificing love for the poor, the outcast and the sick. He lived and died to save us all. But given that true love can only be given freely, He also gave us the freedom to reject His grace; to choose a life without Him. In other words, to choose hell.

I think you get to the point very well when you focus on ‘true love being freely given’. Philosophical arguments and reasoning are not capable of describing the Love of God. It needs to be demonstrated as we find it given to us in the Words and deeds of Christ, and also as it is lived out in the life of the Church today.

One of the greatest authors to describe this love of God for us is S. Bernard of Clairvaux in his famous commentaries (sermons) on the “Song of Songs”. Philosophical speculation gets you almost nowhere when dealing with topics such as the nature and necessity of “Loving Kindness”. S. Bernard details such things by pointing out the historical stories that detail such loving kindness in the patriarchs of the OT, such as Joseph when he was in Egypt, Moses (the most humble man on the Earth), King David a man who frequently wept for his enemies, Job, who was filled with compassion for the poor and was patient to the end. And then, of course… Jesus, who was the kindest of them all. So, philosophy doesn’t work so well when communicating the details of Divine Love. But Bernard’s commentaries on the Song of Songs does a pretty good job of it and is widely/freely available on the Web….for any who are interested in such beautiful subject matter.

So does C.S Lewis and Aquinas go directly against William of Ockham, who proposed voluntarism, saying that, if he wanted, God could have created a universe in which noses would exist.

I like Ockham a lot because of this. I’m wondering how is voluntarism regarded today in the Catholic Church?

Dan,

I’m not sure what word “noses” should have been, but I get the general gist of your question. It’s true that Lewis and Aquinas reject Ockham, and I think rightly so. The problem with separating God’s power from His Nature is that it makes God (and the very idea of God) incoherent. God’s power and His nature — including His nature as Love — are inseparable. It would be wrong to worship a God who was powerful by evil, or good but impotent; so even to refer to God as God (and as a fitting object of our worship) we mean that He’s perfect, omnipotent good… not that He’s just unbridled power.

There’s a much more metaphysical way of approaching this, too. Essence modifies existence – everything that exists, exists as something. In the case of God, however, His essence IS His existence, because He is maximal being.

But this also entails that He is perfect goodness. Why? Because goodness has metaphysical being in its own right, whereas evil is a perversion of good. (Just as a lie is a perversion of the truth; the truth isn’t a perversion of a lie, but has being in its own right). So “maximal being” would be a God who is good, true, beautiful, powerful, etc. But if THOSE things are true of God, then He can’t act contrary to those things while still being those things. Does that make sense? I’m admittedly trying to consolidate a lot of nuanced metaphysical arguments into a paragraph and I’m not doing the arguments justice.

I.X.,

Joe

I suspect that Ockham-style voluntarism is behind a lot of the antinomianism we see today. If Aquinas is right and God’s will, intellect, and love are all inseparable, then God’s commandments are all good and reasonable, and even if we don’t see their purpose or have a hard time keeping them, we can be confident that they are for the best. On the other hand, if Ockham is right and goodness is really just what God arbitrarily wills, then a hard-to-follow teaching just comes to seem like an unjust imposition (because why didn’t God just will something which would be easier for us humans to follow?). Indeed, I would go so far as to doubt that you can really love God as an Ockhamite — you can fear him, certainly, and keep his commandments out of self-interest (because you want to go to Heaven when you die), but love requires us to see the good in the beloved, and if goodness is simply what God arbitrarily wills, how can we meaningfully say that God is good?

Quite so. Did not Christ say that there are things known not to the Son, but only to the Father? Therefore, thou man, shall you enquire of Him? Shall He be enquired of by you, His creature? Has He not provided sufficient proofs for you?

Thus it was said, “Except ye believe as a little child…”

Proofs he will provide to those who seek them in all sincerity, but having seen them and thus believed, we must accept that we cannot and will not know all.

If the very Son of God was satisfied with what His Father provided to Him in understanding, one might think that mortal man could also be satisfied?

Joe,

I think the conclusion of your series on Hell may be summed up as Hell is not a defect in God, nor even a creation of God, but a defect in the will of man. The willing of something than other than God creates a man’s own Hell. Being that the soul is eternal, the ramifications of this are eternal.

This sounds very close to the doctrine of St John the Ladder and other saints who teach that the Light of God is experienced as bliss from the faithful but torture from those who hate God and are apart from His grace.

I read a very interesting article, whose link I lost, where a Protestant (from the Scriptures alone) arrived at precisely this conclusion. The Scriptures are explicit that both reward and punishment come from “the face of the Lord,” that this is experienced as light, and etcetera.

Most people’s objection to the doctrine of Hell comes from 1. a defect in the understanding of human will and 2. not knowing what Hell really is as the Scriptures (and later the fathers) elaborate.

Honestly, my own understanding was very defective until I studied this issue further, arriving to similar conclusions as your articles.

God bless,

Craig

Good summation, Craig. I would only add to the list of objections to the doctrine of Hell: 3) I don’t want it, I don’t believe it, I don’t think I deserve it. Ergo, it can’t possibly exist. 🙂 Perhaps your points 1 and 2 do allow for the inclusion of this sort of objection.

Happy Advent.

I think that works, Margo. 🙂

There are no limits to the power of He who created all. None that mortal man can grasp, and by what presumption shall he speculate upon them?